Discussing how to decolonise the curriculum in the middle of a pandemic might add an extra challenge to an already sensitive task, but as the ASSaM Research Forum created and facilitated by Dr Rebecca Finkel gathers online, it is clear what really happens when people talk about decolonisation in relation to learning, teaching, and researching is about sharing good practice, relating personal stories which are political, and questioning the very meaning of the term. Every so often, a professional experience exceeds expectations to enrich, empower, and energise. Each of us brings their own problematic heritage, subjective experience, and scholarly perception to the topic when engaging in such a conversation, but some of the calls for action in the presentations of Dr Geetha Marcus, Emma Wood, Dr Stefanie Van de Peer, and Dr Caralyn Blaisdell transcended any symbolic boundaries to cultivate empathic understanding.

This forum set out to reflect and build upon the University-wide lightning talks that took place at the end of 2020. In an effort to inform praxis in our various subjects with more and different voices, we seek to capture our impressions of the main ideas here. We have titled this with a nod to the origins of QMU as a cookery school for women. In this regard, we are very much guided by feminist ethics of care, which involve a resistance to the injustices inherent in patriarchy and centre on interpersonal relationships and entangled encounters. Any undertaking with positive social change as its goal may be considered contentious, and this very much has power at its heart. So, we want to draw out some of the insights we picked up and now carry around with us, with the hope that you too will help to carry their weight.

It becomes very clear that there are more nuances to this concept and its application than imagined, especially taking into account different perspectives other than that of the White gaze or the Eurocentric view. Using the term decolonisation instead of diversity or social inclusion is also a conscious choice of politicising and giving power to the critical discourse about personal stories of exclusion which are entangled within wider White supremacy frameworks. As research cannot be and shouldn’t be de-emotionalised, we are all very grateful to listen to each other’s paths of activism, embodiment, and intervention which makes it explicit that there is a deep individual necessity to respond to the call of ‘doing’ something tangible in eradicating colonialism from our pedagogy for good.

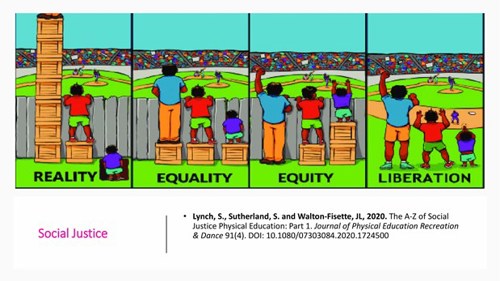

Key questions that were investigated include to what extent is it just the University curriculum that we have to re-examine and not, for example, the HR recruitment systems and/or the research ethics requirements in international settings, as Marcus says? How can we take action to tackle and challenge the White saviour complex and White fragility which, Wood warns, prevents White people from engaging in difficult conversations? As Van de Peer argues, how do we take into account our own positioning in decolonising artistic practices – such as film - and when is the risk of cultural appropriation a calculated one and recognised for what it is, instead of being swept under the carpet? How do we speak about anti-racism and ‘others’ to our children, asks Blaisdell? Which words are really necessary to talk about difficult legacies of White dominance and the power struggle embedded in our systems?

As Marcus points out, questioning the many ways power operates which result in there not being much room for alternatives is a radical, but necessary proposition, as is incorporating and listening to dissenting voices. The complexity of identifying the core actions which can actively generate decolonising practices beyond the forum’s debate is very evident to the speakers and the multidisciplinary group of practitioners/academics invited to contribute to it, while each of us is keen to explore the concrete ways through which we can bring this discussion to fruition and change our very practice.

Indeed, the issues that add to our discomfort are not personal; they are structural. This is behind many other of the recent so-called controversies; for example, ‘Not All Men’ routinely makes the social media rounds in the struggle for gender equality. But, remember, sometimes it’s not about ‘you’. It’s actually about the broken systems. This is best exemplified when Wood quotes Kyle “Guante” Tran Myhre: “White supremacy is not a shark; it is the water.” And how do we ever change the environment, the habitus, the culture and hold those who perpetuate it into account? We need to first acknowledge that we are indeed all swimming in troubled water that needs to become safer for everyone, not just a privileged few who are able to ride the waves unencumbered. And education is central to this. As David Foster Wallace so aptly stated, “It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: This is water. This is water.”

Enabling and facilitating the conversations towards emancipation is certainly an indispensable head start.